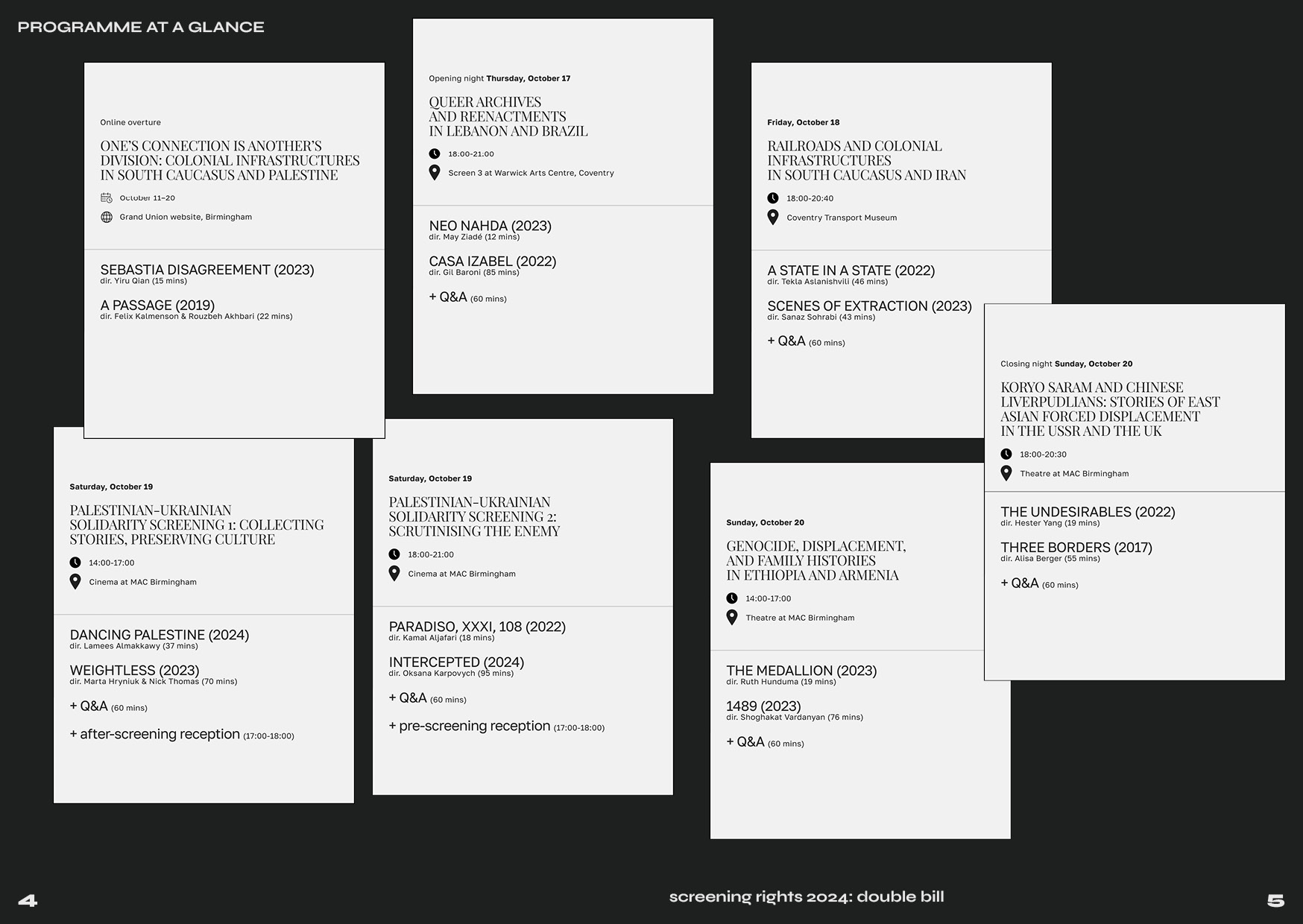

SRFF 2024: DOUBLE BILL — PROGRAMME AT A GLANCE

Online overture

October 11–20

︎ Grand Union website, Birmingham

October 11–20

︎ Grand Union website, Birmingham

ONE’S CONNECTION IS ANOTHER’S DIVISION: COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND PALESTINЕ︎

37 minsSEBASTIA DISAGREEMENT (2023) dir. Yiru Qian (15 mins)

A PASSAGE (2019) dir. Felix Kalmenson & Rouzbeh Akhbari (22 mins)

︎ Watch here

Opening night

Thursday, October 17

︎ 18:00-21:00

︎ Screen 3 at Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry

Thursday, October 17

︎ 18:00-21:00

︎ Screen 3 at Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry

QUEER ARCHIVES AND REENACTMENTS IN LEBANON AND BRAZIL + Q&A︎

NEO NAHDA (2023) dir. May Ziadé (12 mins)

CASA IZABEL (2022) dir. Gil Baroni (85 mins)

︎ Tickets

Friday, October 18

︎ 18:00-20:40

︎ Coventry Transport Museum

︎ 18:00-20:40

︎ Coventry Transport Museum

RAILROADS AND COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND IRAN + Q&A︎

A STATE IN A STATE (2022) dir. Tekla Aslanishvili (46 mins)

SCENES OF EXTRACTION (2023) dir. Sanaz Sohrabi (43 mins)

︎ Tickets

Saturday, October 19

︎ 14:00-17:00

︎ Cinema at MAC Birmingham

︎ 14:00-17:00

︎ Cinema at MAC Birmingham

PALESTINIAN-UKRAINIAN SOLIDARITY SCREENING 1: COLLECTING STORIES, PRESERVING CULTURE + Q&A︎

DANCING PALESTINE (2024) dir. Lamees Almakkawy (37 mins)

WEIGHTLESS (2023) dir. Marta Hryniuk & Nick Thomas (70 mins)

+ Q&A (60 mins)

+ after-screening reception (17:00-18:00)

︎ Tickets

Saturday, October 19

︎ 18:00-21:00

︎ Cinema at MAC Birmingham

︎ 18:00-21:00

︎ Cinema at MAC Birmingham

PALESTINIAN-UKRAINIAN SOLIDARITY SCREENING 2: SCRUTINISING THE ENEMY + Q&A︎

PARADISO, XXXI, 108 (2022) dir. Kamal Aljafari (18 mins)

INTERCEPTED (2024) dir. Oksana Karpovych (95 mins)

+ Q&A (60 mins)

+ pre-screening reception (17:00-18:00)

︎ Tickets

Sunday, October 20

︎ 14:00-17:00

︎ Theatre at MAC Birmingham

︎ 14:00-17:00

︎ Theatre at MAC Birmingham

GENOCIDE, DISPLACEMENT, AND FAMILY HISTORIES IN ETHIOPIA AND ARMENIA + Q&A︎

THE MEDALLION (2023) dir. Ruth Hunduma (19 mins)

1489 (2023) dir. Shoghakat Vardanyan (76 mins)

︎ Tickets

Closing night

Sunday, October 20

︎ 18:00-20:30

︎ Theatre at MAC Birmingham

Sunday, October 20

︎ 18:00-20:30

︎ Theatre at MAC Birmingham

KORYO-SARAM AND CHINESE LIVERPUDLIANS: STORIES OF EAST ASIAN FORCED DISPLACEMENT IN THE USSR AND THE UK + Q&A︎

THE UNDESIRABLES (2022) dir. Hester Yang (19 mins)

THREE BORDERS (2017) dir. Alisa Berger (55 mins)

︎ Tickets

Online overture

October 11-20

︎ Grand Union website, Birmingham

ONE’S CONNECTION IS ANOTHER’S DIVISION:

COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND PALESTINE

SEBASTIA DISAGREEMENT by Yiru Qian (15 mins)

A PASSAGE by Felix Kalmenson & Rouzbeh Akhbari (17 mins)

︎ Watch here

Screening Rights Film Festival 2024: DOUBLE BILL, taking place over the weekend of 17-20 October in Birmingham and Coventry, will be preceded by an online overture hosted by the Birmingham-based arts initiative Grand Union. This will be available on the Grand Union website immediately before and during the festival, from 11 to 20 October. The screening of two short films aims to broaden the context of the in-person events, as well as extend their outreach.

Titled ONE’S CONNECTION IS ANOTHER’S DIVISION: COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND PALESTINE and featuring Sebastia Disagreement by Yuri Qian and A Passage by Felix Kalmenson and Rouzbeh Akhbari, the overture deepens the festival’s engagement with the industrial heritage of the Midlands while also resonating formally and thematically with multiple festival titles.

In particular, it serves as a continuation of a screening on railroads and colonial infrastructures in South Caucasus and Iran, hosted at the Transport Museum in Coventry on 18 October. It also connects with two Palestinian-Ukrainian solidarity screenings (1 and 2), taking place at MAC Birmingham on 19 October, and an event focused on genocide, displacement, and family histories in Ethiopia and Armenia, also at MAC Birmingham, on 20 October.

The overture is designed to give guests a glimpse of the broader programme and to convey the concept behind DOUBLE BILL through a concise and evocative experience lasting about half an hour.

Titled ONE’S CONNECTION IS ANOTHER’S DIVISION: COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND PALESTINE and featuring Sebastia Disagreement by Yuri Qian and A Passage by Felix Kalmenson and Rouzbeh Akhbari, the overture deepens the festival’s engagement with the industrial heritage of the Midlands while also resonating formally and thematically with multiple festival titles.

In particular, it serves as a continuation of a screening on railroads and colonial infrastructures in South Caucasus and Iran, hosted at the Transport Museum in Coventry on 18 October. It also connects with two Palestinian-Ukrainian solidarity screenings (1 and 2), taking place at MAC Birmingham on 19 October, and an event focused on genocide, displacement, and family histories in Ethiopia and Armenia, also at MAC Birmingham, on 20 October.

The overture is designed to give guests a glimpse of the broader programme and to convey the concept behind DOUBLE BILL through a concise and evocative experience lasting about half an hour.

SEBASTIA DISAGREEMENT

Yiru Qian / 2023 / UK / 15’ / Arabic, English with written English

Through highly inventive methods of physical and immaterial visualisation — digital 3D models and screen capture, as well as miniaturised re-enactments using hands, maps, gypsum models, and even puppetry, with marionette oranges serving as stand-ins for the legendary Jaffa fruit — filmmaker-researcher Yiru Quan unpacks the zionist occupation of Masudiya and Sebastia stations, once crucial sites for Palestinian agricultural activities and historically important transit points on the Hejaz railway, which connected cities across North Africa and the Middle East.

A PASSAGE

Felix Kalmenson & Rouzbeh Akhbari / 2019 / Armenia / 17’ / Armenian, Russian, Mandarin Chinese with English subtitles

Oil trucks with Farsi on them, a children’s choir singing in Armenian, an Armenian man singing about the now-discontinued Yerevan-Baku railway in Russian, and the haunting, enigmatic images of two horsemen with mirrors for faces, who search for wind as if to help a nowhere-to-be-seen plane take off and carry a ghostly image of a train through a derelict Soviet-era tunnel — the Meghri region in southern Armenia, which borders Azerbaijan, emerges as a territory in-between languages, cultures, temporalities, and, as discussed by radio hosts in Mandarin Chinese and Russian in the background, neoimperialist geopolitical interests in the South Caucasus and the Middle East.

FILMMAKERS’ BIOS

Yiru Qian is an architect and visual artist who currently lives and works in London. Influenced by her interests in architectural design, archival research, and the archaeology of knowledge, she explores historical narratives that traverse time and space through imagery, mapping, and making.

Pejvak is the long-term collaboration between Felix Kalmenson and Rouzbeh Akhbari. Through their multivalent, intuitive approach to research and living they find themselves in a convergence and entanglement with like-minded collaborators, histories and various geographies.

Opening night Thursday, October 17

︎ 18:00-21:00

︎ Screen 3 at Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry

QUEER ARCHIVES AND REENACTMENTS

NEO NAHDA by May Ziadé (12 mins)

CASA IZABEL by Gil Baroni (85 mins)

+Q&A (60 mins)

︎ Tickets

︎ 18:00-21:00

︎ Screen 3 at Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry

QUEER ARCHIVES AND REENACTMENTS

IN LEBANON AND BRAZIL

NEO NAHDA by May Ziadé (12 mins)

CASA IZABEL by Gil Baroni (85 mins)

+Q&A (60 mins)

︎ Tickets

On the opening night of its 10th anniversary, Screening Rights is staging a special event at Warwick Arts Centre centred around queer archives and reenactments from Lebanon and Brazil and featuring May Ziadé’s short Neo Nahda alongside Gil Baroni’s feature Casa Izabel. Equal parts vivid reconstruction and ingenious fictionalisation of the narratives that have been suppressed or underrepresented due to the turbulent histories of the Middle East and Latin America, Ziadé’s and Baroni’s films, each in their unique way, outline queer genealogies and combat epistemic oblivion.

NEO NAHDA

May Ziadé / 2022 / UK / 12’ / English

In French-Lebanese filmmaker May Ziadé’s Neo Nahda, Mona, a young woman in modern-day London, goes down a rabbit hole of amateur research after coming across photographs of Arab women cross-dressing in 1920s Lebanon. Rich with photographic influences — Maryam Şahinyan, Van Leo, and Marie al-Khazen come to mind — Neo Nahda fuses together images discovered by Ziadé in the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut with inventions of her own. The result is an electrifying queer renaissance of sorts, hinted at in the film’s title (Nahda being the Islamic modernist movement — ‘the Awakening’ — of the early 20th century).

May Ziadé is a French and Lebanese filmmaker and filmworker based in London, whose work “explores the physical and emotional consequences of the cultural and social pressures to conform.”

CASA IZABEL

Gil Baroni / 2023 / Brazil / 85’ / Portuguese with English subtitles

Created in a similarly playful dialogue with the queer narratives of the past, Gil Baroni’s Casa Izabel was loosely inspired by the real-life story of Casa Susanna, a bungalow hidden in the woods of upstate New York where a group of transgender women and cross-dressing men would clandestinely convene and find refuge in the mid-20th century. While its function largely remains the same, in Baroni’s colourful, Almodóvarian comedic thriller, Casa is transported to the depths of the Brazilian forest of the 1960s. The story of the original Casa is given a deliciously dark twist, complicated by jealousy, racial and class tensions, and lurking political intrigue à la Kiss of the Spider Woman. It is a work of speculative fiction that is as indebted to Casa Susanna as it is to the tradition of Brazilian anti-fascist resistance.

Gil Baroni is a writer, director, and producer born in Brazil. His filmography approaches themes surrounding human rights issues, especially minority empowerment, gender equity, the LGBTQI+ universe, and social class struggle.

The screening will be accompanied by video introductions from the filmmakers and followed by a discussion featuring invited guests. The panellists will include guest curator Daniel Zacariotti (Film & TV PhD candidate at Warwick), actress and film curator Sarah Agha (of The Arab Film Club), the Queer Research Network (Airelle Amedro, Aman Sinha, and Polina Zelmanova, all PhD candidates at Warwick), and Misha Zakharov (curator at Screening Rights and Film & TV PhD candidate at Warwick).

GUEST RESPONSES

UNCOVERING QUEER ARCHIVES IS A RADICAL ACT OF RESISTANCE: FILMS OF RESISTANCE RESPONDS TO MAY ZIADE’S NEO

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Films of Resistance is a decentralised community film screening and fundraising resource that believes in the power of cinema to expose, inspire, reflect, frame and reframe; its ability to incite change and resistance on a local and global level. With documentary and fiction films chosen for their artistic impact, the initiative aims to inspire deep thinking, understanding, compassion, and — ultimately — long-term, sustainable and active resistance to the genocide and oppression of the Palestinian people.

Archiving is an addictive form of resistance, especially when you uncover hidden treasures such as those that Mona finds during the course of May Ziadé’s Neo Nahda. Having come across a century-old photograph of cross-dressed Arab women, Mona finds herself feverishly following traces of queer Arab culture in London’s archives. Through an artistic counterpositioning of archival and filmed footage, Ziadé shows the self-exploratory effect of uncovering queer histories from the mainstream historical narrative — a reminder of the power of resistance in revealing alternative histories that global supremacy structures continuously attempt to suppress. Read the full response here︎

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Films of Resistance is a decentralised community film screening and fundraising resource that believes in the power of cinema to expose, inspire, reflect, frame and reframe; its ability to incite change and resistance on a local and global level. With documentary and fiction films chosen for their artistic impact, the initiative aims to inspire deep thinking, understanding, compassion, and — ultimately — long-term, sustainable and active resistance to the genocide and oppression of the Palestinian people.

QUEER REFUGIUM AND RESISTANCE AMIDST FASCIST STATES:

DANIEL ZACARIOTTI INTERVIEWS GIL BARONI ON CASA IZABEL

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Daniel Zacariotti is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of Warwick. His work is focused on queer art forms under far-right and fascist governments in Latin America, with a decolonial and intersectional epistemological approach.

DANIEL ZACARIOTTI INTERVIEWS GIL BARONI ON CASA IZABEL

Set in Brazil in the early 1970s, during the military dictatorship, Casa Izabel depicts a group of men who gather annually, away from society, to cross-dress in a Casa Grande (the term used for the grand houses of slavers in colonial Brazil, as opposed to the Senzalas where the enslaved lived). By encapsulating the possibility of queer existence during a repressive government that enforced the erasure of deviant sexualities and genders, the film presents a contemporary intersectional reading of queerness, race, and class – balancing the film’s 1970s setting with the context of its production and distribution under Bolsonaro’s government. Read the full interview︎

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Daniel Zacariotti is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of Warwick. His work is focused on queer art forms under far-right and fascist governments in Latin America, with a decolonial and intersectional epistemological approach.

Friday, October 18

︎ 18:00-20:40

︎ Coventry Transport Museum

A STATE IN A STATE by Tekla Aslanishvili (46 mins)

SCENES OF EXTRACTION by Sanaz Sohrabi (43 mins)

+ Q&A (60 mins)

+ pre-screnening food reception (17:00-18:00)

︎ Tickets

︎ 18:00-20:40

︎ Coventry Transport Museum

RAILROADS AND COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND IRAN

A STATE IN A STATE by Tekla Aslanishvili (46 mins)

SCENES OF EXTRACTION by Sanaz Sohrabi (43 mins)

+ Q&A (60 mins)

+ pre-screnening food reception (17:00-18:00)

︎ Tickets

Screening Rights Film Festival is bringing the latest socially engaged and formally innovative cinema from the Global South to audiences in the West Midlands. This year, we’re partnering with the Transport Museum in Coventry to stage a site-specific event that engages with the industrial heritage of the Midlands, as well as the British Petroleum archives at the University of Warwick. Titled RAILROADS AND COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND IRAN, it features Tekla Aslanishvili’s A State in a State alongside Sanaz Sohrabi’s Scenes of Extraction—two film essays that evoke detective investigations in the thoroughness of their research. In line with the 2024 festival’s theme, DOUBLE BILL, the screening tackles various geographical contexts that, on closer inspection, can be linked—in this case, British petrocolonialism in Iran and Soviet railroads in the South Caucasus.

A larger context for this screening is provided through an online programme, hosted by Screening Rights in collaboration with the Birmingham-based arts initiative Grand Union, titled ONE’S CONNECTION IS ANOTHER’S DIVISION: COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND PALESTINE, featuring Sebastia Disagreement by Yiru Qian and A Passage by Felix Kalmenson and Rouzbeh Akhbari.

A larger context for this screening is provided through an online programme, hosted by Screening Rights in collaboration with the Birmingham-based arts initiative Grand Union, titled ONE’S CONNECTION IS ANOTHER’S DIVISION: COLONIAL INFRASTRUCTURES IN SOUTH CAUCASUS AND PALESTINE, featuring Sebastia Disagreement by Yiru Qian and A Passage by Felix Kalmenson and Rouzbeh Akhbari.

A STATE IN A STATE

Tekla Aslanishvili / 2022 / Georgia / 47’ / Georgian, Russian, and English with English subtitles

In her symphonic, richly multilingual documentary, Georgian filmmaker Tekla Aslanishvili collects oral testimonies from railway workers, journalists, and researchers who worked on or around the railways that connect(ed) Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan with Russia, Turkey, and Iran. Over time, these railway workers developed chains of solidarity that transcended the politics of the nation-states to which they belonged. Although many of the railways are classified and therefore prohibited from filming, they emerge as somewhat of a protagonist in the film—the titular semi-autonomous “state within a state,” historically an instrument of colonisation, now being used to turn the tables on the oppressors.

Tekla Aslanishvili is an artist, filmmaker and essayist whose works emerge at the intersection of infrastructural design, history and geopolitics.

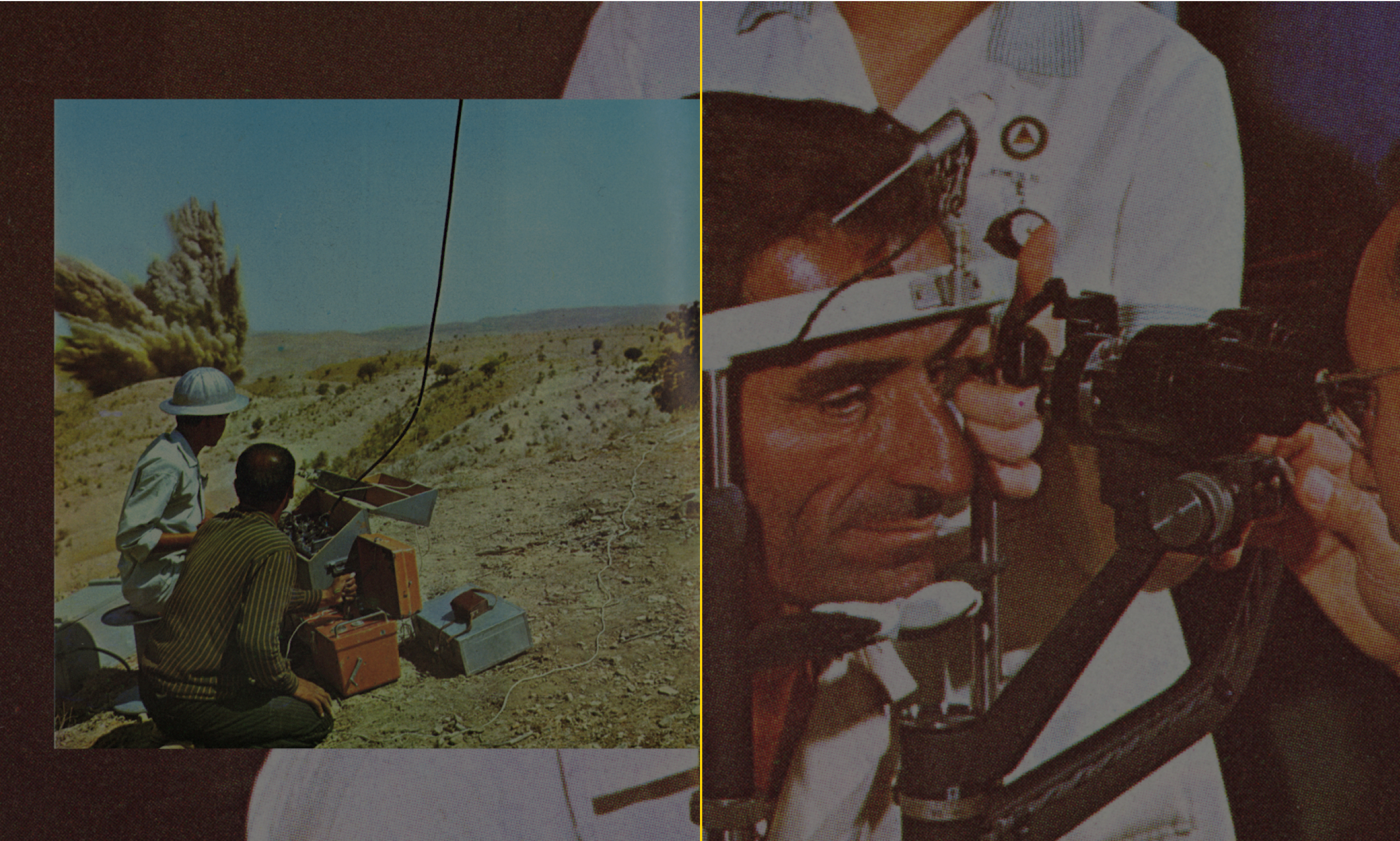

SCENES OF EXTRACTION

Sanaz Sohrabi / 2023 / Canada/Iran / 43’ / English and Farsi with English subtitles

In the second part of her ongoing trilogy on British petrocolonialism in Iran—following the acclaimed One Image, Two Acts (2020)—Iranian filmmaker Sanaz Sohrabi delves deeper into the declassified photographic archives of British Petroleum to uncover haunting stories of labour exploitation, ecological devastation, and extractivism, focussing specifically on the role railroads played within the larger colonial infrastructures. The screening of this work is intended to engage with the industrial heritage of the Midlands, as well as the British Petroleum archives housed at the University of Warwick.

Sanaz Sohrabi is an artist, filmmaker and essayist whose work investigates the impermanence and malleability of historical records and narratives.

The screening will be accompanied by a panel discussion, featuring guest curator Milija Gluhovic, researcher Evelina Gambino, and filmmaker Yiru Qian (more guests TBA). The screening will be preceded by a food reception (17:00-18:00) by the freegan initiative The Real Junk Food Project Central.

ENGINES OF SOLIDARITY:

MILIJA GLUHOVIC INTERVIEWS EVELINA GAMBINO ON A STATE IN A STATE

One of the reasons we have highlighted the stories of infrastructure again is not to idealise a presumably idyllic time of infrastructural life, such as that during the Soviet Union, against the present. Instead, it is to emphasise that, in unfavourable circumstances, both past and present, there is always something excessive, something different. There are always ways in which people can express solidarity with each other, and they can, in fact, create different infrastructural worlds. If we pay attention to these infrastructural worlds and to the logics that govern them, then a better, more equitable vision of infrastructure could potentially emerge. Read the full intervew here︎

Evelina Gambino is the Margaret Tyler Research Fellow in Geography at Girton College, University of Cambridge. Her research is concerned with a situated analysis of global logistics. She has done ethnographic work around several flagship connectivity infrastructures in Georgia and the South Caucasus. In collaboration with artist and director Tekla Aslanishvili she has produced the experimental documentary A State in A State.

Milija Gluhovic is an Associate Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. His research interests include contemporary European theatre and performance, memory studies and psychoanalysis, discourses of European identity, migration and human rights, as well as religion, secularity, and politics.

MILIJA GLUHOVIC INTERVIEWS EVELINA GAMBINO ON A STATE IN A STATE

One of the reasons we have highlighted the stories of infrastructure again is not to idealise a presumably idyllic time of infrastructural life, such as that during the Soviet Union, against the present. Instead, it is to emphasise that, in unfavourable circumstances, both past and present, there is always something excessive, something different. There are always ways in which people can express solidarity with each other, and they can, in fact, create different infrastructural worlds. If we pay attention to these infrastructural worlds and to the logics that govern them, then a better, more equitable vision of infrastructure could potentially emerge. Read the full intervew here︎

Evelina Gambino is the Margaret Tyler Research Fellow in Geography at Girton College, University of Cambridge. Her research is concerned with a situated analysis of global logistics. She has done ethnographic work around several flagship connectivity infrastructures in Georgia and the South Caucasus. In collaboration with artist and director Tekla Aslanishvili she has produced the experimental documentary A State in A State.

Milija Gluhovic is an Associate Professor of Theatre and Performance at the University of Warwick. His research interests include contemporary European theatre and performance, memory studies and psychoanalysis, discourses of European identity, migration and human rights, as well as religion, secularity, and politics.

ON OIL WORKERS’ LABOUR MILITANCY:

AN EXCERPT FROM KATAYOUN SHAFIEE’S MACHINERIES OF OIL

Katayoun Shafiee is an Associate Professor in the History of the Middle East at the University of Warwick. She specialises in the history and material politics of large-scale infrastructures in the modern Middle East. Her first book, Machineries of Oil: An Infrastructural History of BP in Iran (MIT Press, 2018), integrates Middle Eastern history with interdisciplinary approaches in science and technology studies, reconfiguring the politics of the region through an examination of the British-controlled oil industry in Iran.

AN EXCERPT FROM KATAYOUN SHAFIEE’S MACHINERIES OF OIL

Oil’s unique physical and chemical properties demand that each category of work—drilling, pipeline construction, well maintenance, transportation, and refining—utilizes specific kinds of skilled and unskilled laborers such as drillers, pipeline fitters, engineers, geologists, and chemists. The layout and design of oil infrastructure, namely, that it has an enclave character and requires oil wells, a pipeline, and a refinery to transform the oil into marketable products, result in distinct methods of monitoring and surveillance of workers. The oil workers’ capacity to form unions and “engage in strike activity” is drastically reduced, especially when considering that other sources of oil can be relied on and tankers can be rerouted to replace a sudden loss of oil elsewhere. Thus, one reason oil companies have succeeded in making enormous profits has been “their ability to contain labor militancy.” Where labor militancy has occurred, it has generally been concentrated in refinery operations where there are large concentrations of skilled workers who occupy strategic positions to disrupt the economies of both oil-exporting and oil-consuming countries. Over time, pumping stations and pipelines replaced railways as the main means of transporting a liquid form of energy, rather than a solid, from the site of production to refineries and tankers for shipping abroad. This meant the infrastructure of oil operations was vulnerable but not as easy to incapacitate through strike actions as were railways that carried coal, for example. Read the full excerpt here︎

Katayoun Shafiee is an Associate Professor in the History of the Middle East at the University of Warwick. She specialises in the history and material politics of large-scale infrastructures in the modern Middle East. Her first book, Machineries of Oil: An Infrastructural History of BP in Iran (MIT Press, 2018), integrates Middle Eastern history with interdisciplinary approaches in science and technology studies, reconfiguring the politics of the region through an examination of the British-controlled oil industry in Iran.

Saturday, October 19

︎ 14:00-17:00

︎ Cinema at MAC Birmingham

PALESTINIAN-UKRAINIAN SOLIDARITY SCREENING 1: COLLECTING STORIES, PRESERVING CULTURE

DANCING PALESTINE by Lamees Almakkawy (37 mins)

WEIGHTLESS by Marta Hryniuk & Nick Thomas (70 mins)

+ Q&A (60 mins)

+ after-screening reception (17:00-18:00)

︎ Tickets

︎ 14:00-17:00

︎ Cinema at MAC Birmingham

PALESTINIAN-UKRAINIAN SOLIDARITY SCREENING 1: COLLECTING STORIES, PRESERVING CULTURE

DANCING PALESTINE by Lamees Almakkawy (37 mins)

WEIGHTLESS by Marta Hryniuk & Nick Thomas (70 mins)

+ Q&A (60 mins)

+ after-screening reception (17:00-18:00)

︎ Tickets

Screening Rights Film Festival is bringing the latest socially engaged and formally innovative cinema from the Global South to audiences in the West Midlands. The centrepiece of its 10th-anniversary edition, subtitled DOUBLE BILL, consists of two Palestinian-Ukrainian solidarity screenings designed to complement one another. The first of these, featuring Lamees Almakkawy’s Dancing Palestine and Marta Hryniuk’s and Nick Thomas’s Weightless, is dedicated to resisting the perpetual, ages-long genocides through cultural preservation.

Book your tickets for the second screening, featuring Kamal Aljafari’s Paradiso, XXXI, 108 and Oksana Karpovych’s Intercepted, here.

Book your tickets for the second screening, featuring Kamal Aljafari’s Paradiso, XXXI, 108 and Oksana Karpovych’s Intercepted, here.

DANCING PALESTINE

Lamees Almakkawy / 2024 / UK / 37’ / Arabic, English with English subtitles

“When home is gone, the body becomes home.” At the heart of Lamees Almakkawy’s mid-length film essay Dancing Palestine is dabke, historically a workers' dance that has, over time, evolved into a form of remembrance and resistance. Through an ingenious and deeply moving interplay between the material and immaterial, the past and the present, the film combines digital screen-life elements, analogue archives, and dabke performances set against photos of Palestinian landscapes projected onto the dancers’ bodies. Drawing on the same theme of Palestinian cultural preservation that was prominent in last year’s Screening Rights title, Jumana Manna’s Foragers, Almakkawy’s film posits dabke as a defiant, life-affirming celebration of Palestinian culture in the face of its perpetual extermination. Completed as part of her Creative Documentary by Practice MFA at the Anthropology Department of University College London, and realised in close collaboration with Palestinian dabke dancers, Almakkawy’s film premiered at the latest Sheffield Doc, the premier documentary film festival in the UK, where it received a Special Mention prize.

Lamees Almakkawy obtained her Bachelor of Arts in Film and New Media from New York University Abu Dhabi, and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Documentary by Practice from University College London. Her interests lie in the intersection of documentary and fiction filmmaking, focusing on identity, performance, and memory.

WEIGHLTESS

Marta Hryniuk & Nick Thomas / 2023 / Netherlands, Ukraine / 70’ / English, Ukrainian with English subtitles

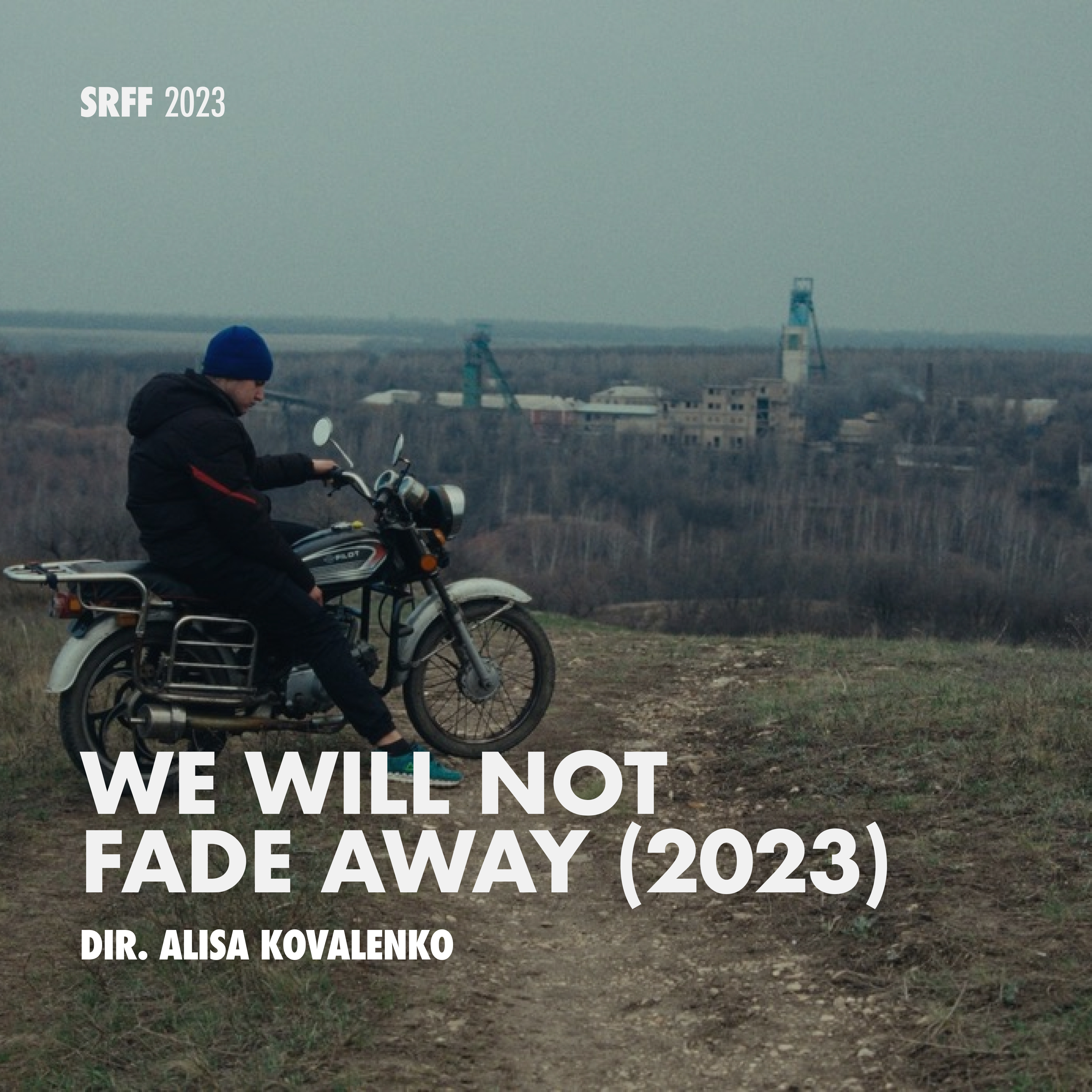

Khrystyna Bunii is an anthropologist who collects the culture of the Hutsuls, a unique ethnographic group of people living in the west of Ukraine. Marta Hryniuk’s and Nick Thomas’s Weightless follows Bunii as she digitises family photos, collects clothes and food recipes, and records tsymbaly music and oral histories of displacement and genocide. What emerges is a fragile yet ever-persistent culture situated at a politically tumultuous crossroads of cultures, languages, and ideologies, one that has been — and continues to be — resisting erasure. While Alisa Kovalenko’s We Will Not Fade Away, screened as part of last year’s Screening Rights, was filmed in the bleak east of Ukraine, where russia’s war has been raging for a decade, Weightless takes place in the breathtaking Carpathian Mountains before the start of the russian full-scale invasion, presenting a different perspective by highlighting the unruly beauty of the natural landscape and Hutsul culture.

Marta Hryniuk and Nick Thomas are visual artists, filmmakers, and cultural organisers based in Rotterdam, where they established the film collective WET film.

The screening will be accompanied by a panel discussion, moderated by Falasteen on Film and featuring guest curator Stefan Lacny (UCL), filmmakers Lamees Almakkawy, Marta Hryniuk and Nick Thomas, and humanitarian expert and healthcare worker Yafa Ajweh. The screening will be followed by a reception (17:00-18:00), featuring traditional food from the the Ukrainian Sunflower and Bayt Al-Yemeni.

LEGACY IN MOTION:

ALA AL-ZENATI RESPONDS TO LAMEES ALMAKKAWY’S DANCING PALESTINE

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Ala Al-Zenati is a Palestinian activist and founder of a community called Jadeela Heritage, which is dedicated to preserving and celebrating Palestinian culture. She focuses on teaching younger generations about the stories and songs passed down from her grandparents, fostering a deeper connection to their heritage.

ALA AL-ZENATI RESPONDS TO LAMEES ALMAKKAWY’S DANCING PALESTINE

The selection of archival images was a meticulous process. Almakkawy sought images that would best support the narrative she wanted to convey—one that depicted Palestinians as more than victims of occupation. She wanted to avoid reinforcing the common narrative of Palestinians as solely defined by their struggles. Instead, she aimed to empower them by showing their vibrant cultural life, their resilience, and their deep love for life. The archival images chosen for the film reflect this approach, depicting Palestinians celebrating, working, and living life to the fullest, often in the face of adversity. Read the full response︎

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Ala Al-Zenati is a Palestinian activist and founder of a community called Jadeela Heritage, which is dedicated to preserving and celebrating Palestinian culture. She focuses on teaching younger generations about the stories and songs passed down from her grandparents, fostering a deeper connection to their heritage.

STEFAN LACNY RESPONDS TO MARTA HRYNIUK’S AND NICK THOMAS’S WEIGHTLESS

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Stefan Lacny is a Lecturer in Russian Culture, Language and Translation at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL. He has recently completed a PhD in Slavonic Studies at the University of Cambridge, where his doctoral research examined Soviet cinematic depictions of Poles and Ukrainians from 1925 to 1941, in the context of the Soviet annexation of eastern Poland in 1939. His interests include Soviet nationalities policies, Stalin-era formulations of Soviet Ukrainian identity and the significance of borders in the Soviet cultural imagination. His article "(Re)discovering Ukrainianness: Hutsul Folk Culture and Ukrainian Identity in Soviet Film, 1939-1941" was published this year in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema.

Through images of long-concealed photographs and recorded folk displays, the documentary showcases the originality of the Hutsuls’ traditional clothing, songs and musical instruments, all shot against a scenic Carpathian background. Yet Hutsul life is far from idyllic. Bunii uncovers the region’s present-day economic difficulties and the persecution of its people under Soviet rule. As Bunii attempts to present the highlanders’ past through their own pictures and words, she is hindered by the Hutsuls’ reluctance to discuss their historical experiences. In this reflection on repression and memory, perhaps the most striking takeaway is the gap of communication and understanding that persists between Ukrainians from the lowlands and the Hutsuls, who remain stubbornly resistant to efforts by outsiders to tell their story. Read the full response︎

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Stefan Lacny is a Lecturer in Russian Culture, Language and Translation at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL. He has recently completed a PhD in Slavonic Studies at the University of Cambridge, where his doctoral research examined Soviet cinematic depictions of Poles and Ukrainians from 1925 to 1941, in the context of the Soviet annexation of eastern Poland in 1939. His interests include Soviet nationalities policies, Stalin-era formulations of Soviet Ukrainian identity and the significance of borders in the Soviet cultural imagination. His article "(Re)discovering Ukrainianness: Hutsul Folk Culture and Ukrainian Identity in Soviet Film, 1939-1941" was published this year in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema.

Guest responses

A key aspect of this year’s festival is the system of guest curation, designed to make the screenings more organic, authentic, and socially responsible. Invited specialists, who are deeply embedded in specific communities—such as academics, activists, community leaders, and creatives—will contribute responses to the films, including essays, lists, poems, interviews, and playlists, and participate in post-screening panels.

Guest curation and responses by Daniel Zacariotti, Films of Resistance, Milija Gluhovic, Ala Al-Zenati, Stefan Lacny, Misha Honcharenko, Pablo Alvarez, Hovsep, Anna-Maria Tesfaye, Misha Zakharov, and Qinghan Chen.

- UNCOVERING QUEER ARCHIVES IS A RADICAL ACT OF RESISTANCE: FILMS OF RESISTANCE RESPONDS TO MAY ZIADE’S NEO NAHDA LINK︎

- QUEER REFUGIUM AND RESISTANCE AMIDST FASCIST STATES: DANIEL ZACARIOTTI INTERVIEWS GIL BARONI ON CASA IZABEL LINK ︎

- ENGINES OF SOLIDARITY: MILIJA GLUHOVIC INTERVIEWS EVELINA GAMBINO ON A STATE IN A STATE LINK︎

- ON OIL WORKERS’ LABOUR MILITANCY: AN EXCERPT FROM KATAYOUN SHAFIEE’S MACHINERIES OF OIL LINK ︎

- A LEGACY IN MOTION: ALA AL-ZENATI RESPONDS TO LAMEES ALMAKKAWY’S DANCING PALESTINE LINK ︎

- MEMORY, IDENTITY, AND THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY: STEFAN LACNY RESPONDS TO MARTA HRYNIUK’S & NICK THOMAS’S WEIGHTLESS LINK ︎

- CINEMATIC CONFRONTATIONS AND IMPERIAL ARCHIVES: PABLO ALVAREZ RESPONDS TO KAMAL ALJAFARI’S PARADISO, XXXI, 108 LINK ︎

- THE VIOLENCE OF SPEECH: MISHA HONCHARENKO RESPONDS TO OKSANA KARPOVYCH’S INTERCEPTED LINK ︎

- MIRACLES DO NOT EXIST: HOVSEP RESPONDS TO SHOGHAKAT VARDANYAN'S 1489 LINK ︎

- SEEING ONESELF IN ANOTHER: ANNA-MARIA TESFAYE RESPONDS TO RUTH HUNDUMA’S THE MEDALLION LINK︎

- TRACING THE UNMOURNED PHANTOM IN AN ERASED HISTORY: QINGHAN CHEN RESPONDS TO HESTER YANG’S THE UNDESIRABLES LINK︎

- BUT WHERE ARE YOU REALLY FROM? MISHA ZAKHAROV RESPONDS TO ALISA BERGER’S THREE BORDERS LINK︎

Guest response

ON OIL WORKERS’ LABOUR MILITANCY: AN EXCERPT FROM KATAYOUN SHAFIEE’S MACHINERIES OF OIL

Oilfields, pipelines, and refineries became the sites of powerful political battles throughout the Middle East in the twentieth century. [...] Oil’s unique physical and chemical properties demand that each category of work—drilling, pipeline construction, well maintenance, transportation, and refining—utilizes specific kinds of skilled and unskilled laborers such as drillers, pipeline fitters, engineers, geologists, and chemists.

The layout and design of oil infrastructure, namely, that it has an enclave character and requires oil wells, a pipeline, and a refinery to transform the oil into marketable products, result in distinct methods of monitoring and surveillance of workers. The oil workers’ capacity to form unions and “engage in strike activity” is drastically reduced, especially when considering that other sources of oil can be relied on and tankers can be rerouted to replace a sudden loss of oil elsewhere.

Thus, one reason oil companies have succeeded in making enormous profits has been “their ability to contain labor militancy.” Where labor militancy has occurred, it has generally been concentrated in refinery operations where there are large concentrations of skilled workers who occupy strategic positions to disrupt the economies of both oil-exporting and oil-consuming countries.

Over time, pumping stations and pipelines replaced railways as the main means of transporting a liquid form of energy, rather than a solid, from the site of production to refineries and tankers for shipping abroad. This meant the infrastructure of oil operations was vulnerable but not as easy to incapacitate through strike actions as were railways that carried coal, for example.

Book your tickets for Scenes of Extraction, Sanaz Sohrabi’s film essay on the British petrocolonialism in Iran, here.

AUTHOR’S BIO

Katayoun Shafiee is an Associate Professor in the History of the Middle East at the University of Warwick. She specialises in the history and material politics of large-scale infrastructures in the modern Middle East. Her first book, Machineries of Oil: An Infrastructural History of BP in Iran (MIT Press, 2018), integrates Middle Eastern history with interdisciplinary approaches in science and technology studies, reconfiguring the politics of the region through an examination of the British-controlled oil industry in Iran.

Guest response

QUEER REFUGIUM AND RESISTANCE AMIDST FASCIST STATES: DANIEL ZACARIOTTI INTERVIEWS GIL BARONI ON CASA IZABEL

Producer and director Gil Baroni gained widespread recognition in 2019 with his third feature film, Alice Júnior, a coming-of-age story about a trans girl preparing for her first kiss in a conservative setting. The film premiered in 2019 as part of the Generation section of the 70th Berlin International Film Festival and won several awards at major Brazilian festivals, including the Felix Award for best national film at the Rio Film Festival and four awards at the Brasília Film Festival. Following Alice Júnior, Baroni continued to focus on queer and dissident narratives, with his latest work, Casa Izabel. Baroni's fourth feature film, which was shot in 2019 and released in 2022, moves away from the upbeat tone of Alice Júnior to explore a more intersectional critique of Brazil's past.

Set in Brazil in the early 1970s, during the military dictatorship, Casa Izabel depicts a group of men who gather annually, away from society, to cross-dress in a Casa Grande (the term used for the grand houses of slavers in colonial Brazil, as opposed to the Senzalas where the enslaved lived). By encapsulating the possibility of queer existence during a repressive government that enforced the erasure of deviant sexualities and genders, the film presents a contemporary intersectional reading of queerness, race, and class – balancing the film’s 1970s setting with the context of its production and distribution under Bolsonaro’s government.

To what extent was Casa Izabel influenced by the book and documentary Casa Susanna?

Casa Izabel was initially the idea of the actress who plays Dália in the film, Laura Haddad. Laura approached Diana, the film’s distributor, and said, “Look, I have this book here, Casa Susanna; it's a book of photographs.” She wanted to bring the concept of a refuge, a retreat for cross-dressers, to Brazil. Diana then got in touch with me, and when she showed me the photos, I immediately said, “I'm interested.” We then brought in Luiz Bertazzo, our scriptwriter, and began a creative process that gradually detached itself from Casa Susanna and became Casa Izabel. I say “detached” because, at the time, we didn’t know who the people in the book were – it was simply an enigmatic collection of photographs.

A book that, at first glance, appeared to be about men who practised cross-dressing, but as the documentary later revealed, it was not only about cross-dressing men but also about the trans women who attended the retreat. Casa Izabel, unlike Casa Susanna, doesn’t focus on trans women but rather on cross-dressing. Our challenge was to develop a script based on these photos and a cast Laura had already suggested. From there, we decided the film had to be set during the dictatorship, reflecting a Brazil under a military coup and the rule of AI-5, yet one that had just won the World Cup. [Institutional Act Number Five, commonly known as AI-5, was the fifth of seventeen extra-legal Institutional Acts issued by the military government in the years following the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état.] This context added depth to our narrative: what if some of these men were in the military and attended this secluded retreat to live out their fantasies? What if, amongst these white men, there was a black character? And what if this house was a former slave house in southern Brazil? The house itself dates back to the period of slavery, located in a region known as ‘Brazilian Europe’. Casa Izabel is an original story created by Luiz Bertazzo, deeply connected to our present and our past.

As you mentioned, the film portrays a highly intersectional reading of Brazil and its era – particularly intertwining queerness and race through the character Leila. Could you elaborate on why this character is present in Casa Izabel?

I see Leila as the protagonist. Leila has a marker that cannot be hidden: her skin colour. She is already excluded from the possibility of escaping into the fantasy that the other characters indulge in when they come to this house to escape their lives and practise cross-dressing. Leila brings discomfort to these characters, who seek to live in a fantasy world within this house. Leila is a boy under the care of his adoptive white mother, who, in the film’s setting, is fated to serve Izabel, the house owner. But Leila subverts this structure. She subverts this logic. She uses debauchery to expose the farce of the other characters, who imagine themselves as actresses and writers. She mocks a structure that is destined to end, a structure that is about to collapse with the end of the dictatorship. It is a structure that will soon open the door to a more racially literate and activist Brazil.

Thus, Leila represents the complexities of racial struggle within Casa Izabel. She embodies the rupture of white hegemony, of a master-servant dynamic. Leila also signifies the end of this house. In keeping with the film's narrative, which unfolds over the course of a day and ends with the house in flames, Leila questions the house’s inability to evolve, despite having had its glory days. For me, this body, this character, is a challenge in the sense that she is always mocking and aware of being an uncomfortable presence. Leila shows that this house is not inviolable, as an undercover government agent will later confirm in the film. Leila breaks the sanitised view of white private property as something sacrosanct. The house, initially perceived as a place of refuge and safety, reveals its flaws and corruption as Leila charts her course through it. It is a house that shelters military officers. It is a slave house. It is a house full of murderers. Leila broadens the conversation around Casa Izabel: it is not just a film about cross-dressing, but about race, affection, and resistance – a film that balances vulnerability and strength.

Although set during the dictatorship, Casa Izabel was filmed at the start of Bolsonaro’s administration in 2019 and premiered at the end of his government in 2022. How does the film reflect those times?

Casa Izabel undoubtedly interrogates both the period in which its characters exist and the time in which the film is being released. We must revisit the far right and Brazilian fascism because they are still very much part of our daily lives. Bolsonaro’s administration was a form of fascism, though not experienced in the same way as traditional fascism or as it was known during the dictatorship. It was a complete corruption of institutions, disguised as a defence of the family, good morals, and Christian values. It appropriated arguments that were dear to society and turned them into instruments to promote violent ideals. Casa Izabel questions this argument through three elements central to society: the territory, the house, and the body. We are dealing with a territory under military rule, a house with slaveholding roots, and queer and black bodies. In other words, we are centring dissident bodies in the narrative to challenge fascist values. Casa Izabel becomes an outcry, a return to a violent past in an attempt to understand a repressive present. The idea was conceived before Bolsonaro’s government, filmed during it, and released at its end.

So, the film is not just an attempt to understand the past but to position itself in an increasingly uncertain present. Moreover, through the house’s space, we offer a critique of Brazil’s distant yet still present past: the slave-owning roots of colonial Brazil. This is why it was crucial for us to position Leila as the protagonist and the only black character, the one who ignites the fire that burns the house at the end. This past must be destroyed; its roots must cease to exist entirely. There can be no room for these values in contemporary Brazil. This rupture must be decisive and everlasting. The central message of the film is precisely this: resilient bodies, which even today suffer oppression, take into their own hands the means to destroy those who ostracise them.

How have the critics and audience perceived the film?

The film has had an exciting run at festivals. In its debut at CINE PE, one of the most important festivals in Brazil, it won five awards, including Best Film. Overall, the reactions have often been dichotomous. Some use great superlatives that impress me, while others say the film tries to tackle too many themes and becomes confusing. However, I see the value in these layers; after all, they reflect our society. We've had incredible screenings, such as the opening session of the 12º Olhar de Cinema – Festival Internacional de Cinema de Curitiba, at the Ópera de Arame in Curitiba, in front of more than 1,600 people. We've also received some negative feedback from festivals, which, to me, confirms the relevance of Casa Izabel. After all, it’s cinema’s role to question spaces, and, in turn, to be questioned.

Considering that this interview is directed towards Screening Rights Film Festival in the United Kingdom, is there any message you want people to take from the film and this interview?

Well, you're in a land of significant colonisers. I don’t think we can ignore the fact that colonisation is inseparable from slavery. That must never be forgotten. Furthermore, we need to be actively engaged with social movements and the resistance and ruptures they create. Only then will one message be clear: people will not give up the rights they have fought for. And they won’t stop until we all share the same rights; we want nothing less. It’s time to listen to those who have been continuously silenced and to stop any attempt to silence them.

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Daniel Zacariotti is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of Warwick. His work is focused on queer art forms under far-right and fascist governments in Latin America, with a decolonial and intersectional epistemological approach.

Daniel Zacariotti

Gil Baroni

Guest response

A LEGACY IN MOTION: ALA AL-ZENATI RESPONDS TO LAMEES ALMAKKAWY’S DANCING PALESTINE

Dancing Palestine is a 37-minute documentary that explores the deep cultural resilience embodied in the traditional Palestinian dance, dabke. The film poignantly captures how this dance has transcended its origins to become a powerful form of resistance and a vessel for collective memory among Palestinians, who face not only land occupation but also continuous socio-political challenges and threats of cultural erasure.

The documentary opens by shedding light on the scarcity of accessible Palestinian archival materials. Many of these archives have been destroyed, hidden, or remain inaccessible, an attempt to erase the evidence of Palestinian existence on their land. This is one of the major challenges in finding neutral archives that depict Palestinians simply living their lives, as noted by the director, Lamees Almakkawy. However, the film also highlights the efforts of incredible communities who are working to make their personal family archives available to the public. These efforts aim to counter the narrative that Palestine never existed, or that Palestinians lacked a rich culture.

As the camera pans across several archival images that vividly depict the cultural memory of Palestine, the narrator introduces the roots of dabke. Originally a communal dance among workers and communities before the Nakba, dabke has evolved into a cultural symbol that embodies Palestinian heritage and has become closely associated with resistance, particularly after the Nakba. Almakkawy carefully selected these images to ensure they depicted Palestinians in their natural state, outside the context of occupation, to show them as a standalone identity. This approach was crucial to Almakkawy, who sought to tell the story of Palestinians living their lives, celebrating their culture, and preserving their identity through dance.

The director masterfully blends archival footage of Palestinian families simply living their lives with intimate interviews of dabke dancers. These dancers emphasize that dabke has grown beyond its role as a traditional dance, now serving as a means of cultural preservation and resistance—a form of archiving in itself. When asked about the inspiration behind Dancing Palestine, Almakkawy explained:

“I was curious about the dance because I knew there was a political undertone to it. You can tell by the lyrics of the songs and the movements in the dance. I wanted to understand the history behind the dance, why it is significant to Palestinians, and why they perform it everywhere. This led me to start my research, and in general, my work focuses on performance, identity, and collective memory. Dabke was the perfect combination of all these elements.”

To ensure authenticity in representing Palestinian experiences, Almakkawy immersed herself in various forms of Palestinian storytelling. She attended performances, exhibitions, and shows, listening closely to how Palestinians narrate their own history. This deep engagement with Palestinian voices was fundamental to her creative process, allowing her to build the documentary’s narrative from a place of respect and understanding. Almakkawy conducted conversations with dabke dancers, academics, and researchers, which served as the backbone of the film. From these interviews, she carefully extracted parts that formed the foundation of the documentary, aligning them with archival materials that reflected the Palestinian narrative.

In a particularly striking segment, the documentary showcases dabke dancers in the diaspora, capturing them as they choreograph new dances. Almakkawy felt it was essential to not only show the performances but also the creative process behind them—the careful consideration of each movement, and the stories these movements tell. By filming the dancers as they create, the documentary provides a window into how dabke continues to evolve as a living tradition, constantly adapting to new contexts while remaining rooted in the past.

The selection of archival images was a meticulous process. Almakkawy sought images that would best support the narrative she wanted to convey—one that depicted Palestinians as more than victims of occupation. She wanted to avoid reinforcing the common narrative of Palestinians as solely defined by their struggles. Instead, she aimed to empower them by showing their vibrant cultural life, their resilience, and their deep love for life. The archival images chosen for the film reflect this approach, depicting Palestinians celebrating, working, and living life to the fullest, often in the face of adversity.

Almakkawy’s deliberate choices in both the archival material and the documentary’s structure align with her overarching message: Palestinians should not be victimized. She emphasized that throughout the filmmaking process, she was mindful of avoiding the typical narrative that tends to victimize Palestinians. “I think a lot of times when you see stories about Palestine, they tend to follow a similar narrative, one that often results in victimizing Palestinians,” she noted. “I didn’t want to victimize them—I wanted to empower them. I don’t think Palestinians want our pity; they want us to act so that they won’t disappear. The biggest takeaway from this film is that Palestinians just want to live their lives. They have a deep love of life, and they insist on living it. We just need to allow them to live.”

The documentary effectively conveys this message, illustrating how dabke has become a tool not just for cultural preservation but also for asserting identity and resisting erasure. Through its careful combination of archival images, interviews, and dance performances, Dancing Palestine tells a story of resilience, creativity, and the enduring spirit of a people determined to preserve their heritage and identity against all odds.

By the film’s conclusion, viewers are left with a profound understanding of how dabke embodies the Palestinian struggle and their unwavering determination to maintain their culture. Almakkawy’s vision for Dancing Palestine is clear: to portray Palestinians as vibrant, resilient people who refuse to be defined by their circumstances. Through dabke, they assert their existence, their history, and their right to live and thrive on their own terms.

Ultimately, Dancing Palestine serves as a testament to the power of art as a form of resistance and the importance of cultural preservation in the face of ongoing challenges. Almakkawy’s documentary is not just a film about a dance; it is a powerful statement on the resilience of the Palestinian people and their unyielding commitment to preserving their identity and heritage for future generations.

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Ala Al Zenati is a Palestinian activist and founder of a community called Jadeela Heritage, which is dedicated to preserving and celebrating Palestinian culture. She focuses on teaching younger generations about the stories and songs passed down from her grandparents, fostering a deeper connection to their heritage.

Ala Al Zenati

Guest response

CINEMATIC CONFRONTATIONS AND IMPERIAL ARCHIVES:

PABLO ALVAREZ RESPONDS TO KAMAL ALJAFARI’S PARADISO, XXXI, 108

Images are instrumental sources of evidence in chronicling global conflicts. Without them, recent or past wars hardly exist in the imaginary of distant spectators. But precisely because of their indexical value, images of war are perpetually subjected to interpretation and manipulation. They inevitably enter what Jane Gaines refers to as a “war on images”, where they are used ideologically to either reproduce or refute hegemonic frameworks and political discourses.

In a recent TV interview, an Israeli soldier condemned the leaking of CCTV footage involving an alleged sexual assault on a Palestinian prisoner during the ongoing genocide in Gaza. For the soldier, this footage – which captures soldiers covering the alleged assault with their riot shields – “slanders the name [of the IDF] in the world”, which according to him is “a very healthy army”. Of course, the “name” being slandered here is, as the CCTV footage and multiple human rights organisations have documented over decades, based on a constructed reality; a discourse that legitimises military occupation and abstracts imperial violence in Palestine. The publication of this footage risks exposing a fissure in this imperial discourse, where the IDF’s self-representation collides with the (indexical) reality beneath it.

This dichotomy between the reality and representation of war underlies Kamal Aljafari’s recent short film, Paradiso, XXXI, 108 (2022). The film repurposes Israeli propaganda films commissioned by the Israeli Army during the 1960s and 1970s. In these materials, the IDF is portrayed in the same positive light as imagined by the aforementioned soldier: as a modern, precise, and sophisticated army driven by collective effort, a strong sense of camaraderie, and mastery of state-of-the-art war technology. The footage shows IDF soldiers and war machinery advancing fearlessly across the hostile desert of Al-Naqab in battle against an enemy that is never seen, always distant and hidden. This narrative, in an unequivocally Orientalist tone, evokes the heroic endeavour of a modern and “healthy” IDF during the 1967 war against Israel’s “primitive” and “threatening” Arab neighbours. It also perpetuates the Zionist myth of Palestine as a “land without a people”, a trope that legitimises Israel’s occupation and its settler-colonial project.

Paradiso appropriates and reworks these overtly propagandistic images through various editing techniques, thus transforming their purpose and turning them into a ‘fictional drama of men playing at war’. By re-ordering the footage or replacing the voiceover narration with elegiac classical music, the film creates an almost burlesque and absurd narrative of the already picturesque depictions of the IDF. Through this playful editing, Aljafari poses serious questions regarding the status of war images. “Was then Your image like the image I see now?” wonders the pilgrim contemplating the imprint of Christ’s face on the Veil of Veronica in Paradiso, the passage from Dante’s Divine Comedy that gives the title to Aljafari’s short film and is also referenced in a short story by Borges. Like Dante’s Paradiso, Aljafari’s film interrogates the reality of the image fabricated by the IDF in these fictional films.

Set within a new cinematic context, these heroic images further reveal their function as what Ariella Azoulay (2019) describes as “another imperial technology” used to abstract and reproduce imperial violence. When re-edited and reduced to the absurd, the violence underlying these images is not only exposed but reversed, confronting the imperial discourse embedded within them.

In fact, this confrontation is also inherent in the filmmaker’s mere appropriation and manipulation of the archival military footage. Paradiso is part of a series of cinematic interventions made by Aljafari over the last decade in response to the Israeli colonial archive. In his 2015 film Recollection, Aljafari erases Israeli actors from scenes of fictional films shot in Jaffa, his hometown, in a decolonial practice that foregrounds “invisible” Palestinian “extras” otherwise relegated to the background of these films by zooming in on them. In a more recent work, Aljafari digitally defaces characters from Israeli fictional and non-fictional footage and recovers Palestinian archives looted and stored by Israel during the 1982 invasion of Lebanon. With Paradiso, Aljafari continues his archival film practice, which he describes as a “work of sabotage against the colonial archive”. As a Palestinian with very limited access to colonial archives, Aljafari’s re-editing of military fictional footage constitutes a political gesture in itself—an act of sabotage against colonial hegemonic archival practices and conditions. In this sense, Paradiso intervenes both discursively/cinematically and materially/archivally by subverting the violent meanings of these fictional films while challenging their location and ownership.

GUEST CURATOR’S BIO

Pablo Alvarez is an independent researcher and film worker with an interest in the relationship between cinema, history, human rights, and social change. He is the co-director of Falasteen on Film, a community cinema showcasing Palestinian films in Birmingham, and also serves as a coordinator at Screening Rights.

Pablo Alvarez

SRFF 2024 TRAILER

What is SRFF?

Screening Rights Film Festival (SRFF) is the West Midlands’ festival of socially engaged and formally innovative cinema from the Global South.

It was founded in 2015 by Professor Michele Aaron, then a Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Birmingham, now a Professor in Film & TV Studies at the University of Warwick. Initially hosted at various venues in Birmingham, SRFF expanded to include Coventry in 2018, and an online edition took place in 2020. Situated at the intersection of art, academia, and activism, the festival is primarily funded by the Warwick Institute of Engagement, with occasional support from Film Hub Midlands.

SRFF is known for showcasing a diverse range of films that explore human rights and social justice issues, from historical atrocities to contemporary stories of activism, engaging with some of the most urgent issues of the past, present, and future. The festival aims to foster connections within and between the local communities and initiatives of the West Midlands, create space for critical thinking, and offer tools for direct action. The focus is not only on the films but also on the post-screening Q&A sessions and audience participation. All screenings at the festival include special events with panel discussions featuring experts on the topics raised by the films.

ARCHIVE

SRFF 2024: DOUBLE BILL

CURATORIAL STATEMENT

Screening Rights, a festival of socially engaged and formally innovative cinema from the Global South, returns with a new, highly ambitious and conceptual 10th-anniversary edition, which will take place from 17-20 October in Birmingham and Coventry.

Solidarity Through Mutual (Un)learning

In line with this year’s subtitle and theme, DOUBLE BILL, we will be screening films from seemingly different and sometimes geographically distant contexts that, in fact, share much in common—such as struggles, traumas, and cultural similarities. Each screening will pair a feature with a short film or present a series of mid-length moving image works that are intended to complement, echo, and enhance one another. We are particularly interested in promoting South-to-South solidarity through mutual (un)learning between countries and populations in East and West Asia, East Africa, and Latin America on the one hand, and those in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the South Caucasus on the other. The motif of duality and doubling is highlighted through our visuals, namely golden lines dissecting film stills in two.

What’s On

The festival comprises 14 films in total, with two screenings in Coventry, at the Warwick Arts Centre and the Coventry Transport Museum, and four in Birmingham, once again taking place at the Midlands Arts Centre, a local favourite. Most of the films are cutting-edge festival titles from Palestine, Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Brazil, Ethiopia, Iran, and more, released in the last two years and never before screened in Birmingham or Coventry. A new addition to the festival is the online screening of two shorts, staged in collaboration with the Birmingham-based arts initiative Grand Union, which will take place on the Grand Union website immediately before and during the festival, from 11-20 October. It is designed to offer a glimpse of the broader programme and convey the concept behind DOUBLE BILL through a concise and evocative experience lasting about half an hour. While engaging with the local industrial context and serving as a continuation of our event on colonial railroads, it is also aimed at expanding our outreach to larger audiences.

Guest Curation

A key aspect of this year’s festival is the system of guest curation, designed to make the screenings more organic, authentic, and socially responsible. Invited specialists, who are deeply embedded in specific communities—such as academics, activists, community leaders, and creatives—will contribute responses to the films, including essays, lists, poems, interviews, and playlists, and participate in post-screening panels.

Celebration of Commonalities, Recognition of Differences

Running through these six in-person and one online event is the celebration of commonalities and the recognition of differences. How do we stand in solidarity with one another in times of apartheid, disinformation, and double standards? How can we move beyond the binary thinking of the Cold War and recognise systems of oppression (and resistance) as intersecting parts of a larger whole? By bringing various communities together and facilitating vibrant, diverse, and cross-pollinating events, we aim to activate a process of learning (and much-needed unlearning)—a temporary utopia where voices that do not necessarily align can be heard together through thoughtful organisation. The festival is thus at once a community gathering and an educational event: similar to the model introduced by one of the festival’s titles, Tekla Aslanishvili’s brilliant study of railroads in the South Caucasus, A State in a State, it is a symphony that celebrates the multiplicity of human experience and resistance.

From Ukraine to Palestine, Occupation Is a Crime

Drawing on the topics that the festival has engaged with in previous years, SRFF 2024 reaffirms its commitment to certain struggles. Our opening night, dedicated to queer archives and reenactments, features Gil Baroni’s Casa Izabel, a colourful, Almodóvarian comedic thriller about queer resistance in Brazil and a spiritual successor to last year’s title, Sebastien Lifshitz’s Casa Susanna. The festival once again explores the occupation of Artsakh through the screening of Shoghakat Vardanyan’s 1489, a deeply moving and intimate first-person account of Azerbaijani aggression, which was awarded the main prize at IDFA, the world’s premier documentary film festival. Continuing our prior engagement with ESEA communities in Birmingham and Coventry, we’re also exploring the long-classified story of the racialised forced displacement of the Chinese Liverpudlians in Hester Yang’s The Undesirables. At the crux of SRFF 2024: DOUBLE BILL are two Palestinian-Ukrainian solidarity screenings meant to complement one another: the first celebrates Palestinian and Hustul cultures (Lamees Almakkawy’s Dancing Palestine and Marta Hryniuk’s and Nick Thomas’s Weightless), while the other militantly demystifies russian and zionist propaganda (Oksana Karpovych’s Intercepted and Kamal Aljafari’s Paradiso, XXXI, 108).

Site Specificity: Railroads, Industrial Infrastructures, and The British Petroleum Archives

If last year we engaged with the University of Warwick premises as part of a mediated tour around its art collection, this year we’re focusing on the industrial and transportation context of the Midlands by organising a series of online and in-person events about railroads in collaboration with the Transport Museum in Coventry and Grand Union in Birmingham. Specifically, we’re interested in examining the histories of British colonial infrastructures in Iran and Palestine (Sanaz Sohrabi’s Scenes of Extraction and Yiru Qian’s Sebastia Disagreement) and Soviet and russian colonialism in the South Caucasus (Tekla Aslanishvili’s A State in a State and Felix Kalmenson’s and Rouzbeh Akhbari’s A Passage). These events are particularly fitting as the University of Warwick was formerly sponsored by British Petroleum and still holds the BP archives that are accessible only to accredited researchers.

Research ⮂ Practice

At least three films at this year’s Screening Rights — Sebastia Disagreement, Dancing Palestine, and The Undesirables — were realised within academic infrastructures as part of practice-based MA programmes, while some of the others are the result of close collaboration with researchers and archives (A State in a State, A Passage, Scenes of Extraction, Neo Nahda, Weightless, Paradiso, Casa Izabel) or oral testimonies (Intercepted, 1489, The Medallion, Three Borders). In this regard, the festival — a hybrid endeavour in itself, partially funded by and originating from the University of Warwick — aims to connect local communities with the worlds of filmmaking and academia, while supporting the work of recent graduates, early-career filmmakers, and video artists, and expanding the boundaries of artistic research.

Bittersweet symphony

DOUBLE BILL is a theme open to experimentation, and even somewhat playful, which is particularly helpful when dealing with hard-hitting, challenging subject matter. Alongside feelings of anger and indignation, we also wanted to leave space for pensiveness, curiosity, and joy (reflected in our poster, featuring a still with Neo Nahda’s self-styled archivist protagonist). Admittedly, some events are difficult to “enjoy” in the traditional sense (and certain screenings even contain trigger warnings), but we hope that the audiences of the West Midlands learn something new and appreciate some of the most innovative works of socially engaged filmmaking in recent years.

The festival was researched, conceived, and facilitated by Misha Zakharov as part of his ongoing practice-based PhD project in Film & TV Studies at the University of Warwick. It was coordinated by Dr Pablo Alvarez and directed by Professor Michele Aaron.

STATEMENT OF SOLIDARITY

The festival unequivocally stands with all oppressed groups whose stories it is indebted to: those fighting russian and western imperialism, those forcibly displaced, and queer and trans people.

Deeply moved and inspired by the Ukrainian Letter of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, the history of Crimean Tatar and Palestinian solidarity, and the stories of Palestinian-Ukrainians, we are centring both Palestine and Ukraine as part of our festival. As an initiative aimed at knowledge production, Screening Rights supports the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) and is proud to screen moving images works highlighting 76 years of “israeli” occupation and the ongoing genocide of Palestinians, such as Paradiso, XXXI, 108, Dancing Palestine, and Sebastia Disagreement. Facilitated by a queer-identifying russian-born person of colour, the festival also supports the Ukrainian boycott of russian cultural production and is immensely grateful to present films that demystify and combat russian imperialism, such as Intercepted, Weightless, A State in a State, and Three Borders.

We are privileged to have the platform and resources to process the ongoing russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the “israeli” genocide of the Palestinian people, as well as the wave of racist pogroms and horrific acts of anti-trans violence in the UK. While we redistribute these resources — financial and intellectual — among audiences beyond the historically elitist context of British academia, we also recognise the limits of our own positionality. We acknowledge the University of Warwick’s complicity in the genocide of the Palestinian people through its continued financial ties with Moog, Rolls-Royce, and BAE Systems. We also recognise its former ties to the ecologically devastating British Petroleum (as well as the fact that Warwick still holds the BP archives on its premises), which became the impetus of our site-specific events on colonial infrastructures. Many struggles are beyond the scope of this year’s festival, such as those in Sudan and Congo, Rojava, Kashmir and East Turkestan, as well as the struggles of indigenous peoples in what are known as “russia”, “the united states of america”, “canada”, “australia”, and “new zealand”.

We urge you to donate to organisations that directly support the people related to the screenings, such as Vsesvit, kharpp, Queersvit, and Eurorelief. We hope that the guest responses accompanying the festival will offer suggestions that can enrich its context and provide further tools for exploring the issues it raises.

Deeply moved and inspired by the Ukrainian Letter of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, the history of Crimean Tatar and Palestinian solidarity, and the stories of Palestinian-Ukrainians, we are centring both Palestine and Ukraine as part of our festival. As an initiative aimed at knowledge production, Screening Rights supports the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) and is proud to screen moving images works highlighting 76 years of “israeli” occupation and the ongoing genocide of Palestinians, such as Paradiso, XXXI, 108, Dancing Palestine, and Sebastia Disagreement. Facilitated by a queer-identifying russian-born person of colour, the festival also supports the Ukrainian boycott of russian cultural production and is immensely grateful to present films that demystify and combat russian imperialism, such as Intercepted, Weightless, A State in a State, and Three Borders.

We are privileged to have the platform and resources to process the ongoing russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the “israeli” genocide of the Palestinian people, as well as the wave of racist pogroms and horrific acts of anti-trans violence in the UK. While we redistribute these resources — financial and intellectual — among audiences beyond the historically elitist context of British academia, we also recognise the limits of our own positionality. We acknowledge the University of Warwick’s complicity in the genocide of the Palestinian people through its continued financial ties with Moog, Rolls-Royce, and BAE Systems. We also recognise its former ties to the ecologically devastating British Petroleum (as well as the fact that Warwick still holds the BP archives on its premises), which became the impetus of our site-specific events on colonial infrastructures. Many struggles are beyond the scope of this year’s festival, such as those in Sudan and Congo, Rojava, Kashmir and East Turkestan, as well as the struggles of indigenous peoples in what are known as “russia”, “the united states of america”, “canada”, “australia”, and “new zealand”.

We urge you to donate to organisations that directly support the people related to the screenings, such as Vsesvit, kharpp, Queersvit, and Eurorelief. We hope that the guest responses accompanying the festival will offer suggestions that can enrich its context and provide further tools for exploring the issues it raises.

ACCESSIBILITY

The venues hosting our screening events — Warwick Arts Centre, Coventry Transport Museum, and MAC Birmingham — are equipped to provide an accessible environment for audiences with disabilities, including wheelchairs available for visitors and accessible toilets. We will do our utmost to meet any access requirements to ensure no one is excluded. All three of our venues have lift access, and one has step-free access to the screening room. The three screens at the Warwick Arts Centre have designated seating for attendees with disabilities and step-free access via lift. The Midlands Arts Centre has installed two types of induction loop systems for visitors with hearing impairments, and its cinema also has designated wheelchair spaces that are kept off general sale.

Every film will be shown with English subtitles and/or in a captioned version to accommodate audiences with hearing impairments, as well as visitors whose first language is not English.

We’re keen to foster connections within and between communities, so if you’d like to attend the screenings as a group, we can offer promo codes for discounted tickets, as well as free tickets for unwaged persons and those in need.

Please email Screening Rights curator Misha Zakharov (misha.zakharov@warwick.ac.uk) and the festival coordinator Pablo Alvarez (pabloalvarezmurillo@gmail.com) for more details.

Every film will be shown with English subtitles and/or in a captioned version to accommodate audiences with hearing impairments, as well as visitors whose first language is not English.

We’re keen to foster connections within and between communities, so if you’d like to attend the screenings as a group, we can offer promo codes for discounted tickets, as well as free tickets for unwaged persons and those in need.

Please email Screening Rights curator Misha Zakharov (misha.zakharov@warwick.ac.uk) and the festival coordinator Pablo Alvarez (pabloalvarezmurillo@gmail.com) for more details.

HOW TO FIND US

The directions to our three venues can be accessed on their respective websites:

Warwick Arts Centre

One alternative route to the Warwick Arts Centre for those travelling from other cities would be to disembark at Canley train station and take a 30-minute walk to the Warwick campus.

Coventry Transport Museum

MAC Birmingham

Warwick Arts Centre

One alternative route to the Warwick Arts Centre for those travelling from other cities would be to disembark at Canley train station and take a 30-minute walk to the Warwick campus.

Coventry Transport Museum

MAC Birmingham

VOLUNTEER WITH US

SRFF 2024 is looking for volunteers—film buffs, socially engaged citizens, and students—in Birmingham, Coventry, and the surrounding areas, to help greet our guests, distribute brochures and questionnaires before and after screenings, assist during post-screening discussions, and capture on-site photos and videos for our social media accounts. We’re offering free tickets to festival screenings and can cover your travel expenses—please email Screening Rights curator Misha Zakharov (misha.zakharov@warwick.ac.uk) and the festival coordinator Pablo Alvarez (pabloalvarezmurillo@gmail.com) for more details.

In line with this year’s programme, we are particularly eager to work with volunteers whose background or interests lie in the following regions:

— East Asia (especially China);

— Eastern Europe (especially Ukraine);

— Central Asia (especially Uzbekistan);

— South Caucasus (especially Armenia and Georgia);

— Latin America (especially Brazil);

— West Asia (especially Iran, Lebanon, and Palestine);

— East Africa (especially Ethiopia).

In line with this year’s programme, we are particularly eager to work with volunteers whose background or interests lie in the following regions:

— East Asia (especially China);

— Eastern Europe (especially Ukraine);

— Central Asia (especially Uzbekistan);

— South Caucasus (especially Armenia and Georgia);

— Latin America (especially Brazil);

— West Asia (especially Iran, Lebanon, and Palestine);

— East Africa (especially Ethiopia).

PARTNERS

Financial partners

Warwick Institute of Engagement

Film Hub Midlands

Organisational partners

Warwick Arts Centre